The Parking Lot and the Problem

September 2024

I sit in my car in the Thompson Rivers University parking lot, engine off, coffee gone cold in the cup holder. Through the windshield, I can see students hurrying across campus, backpacks heavy, faces down against the wind. Some of them are my students. Some of them might have been my students last semester, but I was not rehired for that particular course this term. In seventeen years as contract faculty, I have learned not to take it personally when courses disappear from my teaching load. The university operates on logic I cannot always predict.

This morning, I am supposed to teach organizational behaviour and business ethics. I am supposed to stand in front of a classroom and explain concepts like organizational justice, the idea that fair treatment within institutions requires three elements: distributive justice (fair allocation of resources), procedural justice (fair processes for decision-making), and interactional justice (respectful interpersonal treatment) (Greenberg, 1987). I am supposed to teach care ethics, the philosophical framework developed by scholars like Nel Noddings (2013) that positions caring relationships as the foundation of moral action. I am supposed to help students understand how organizations can create cultures of accountability, reciprocity, and genuine belonging.

The contradiction sits heavily in my chest. How do I teach justice within a system structured against it? How do I teach care ethics while participating in structures that systematically exclude care?

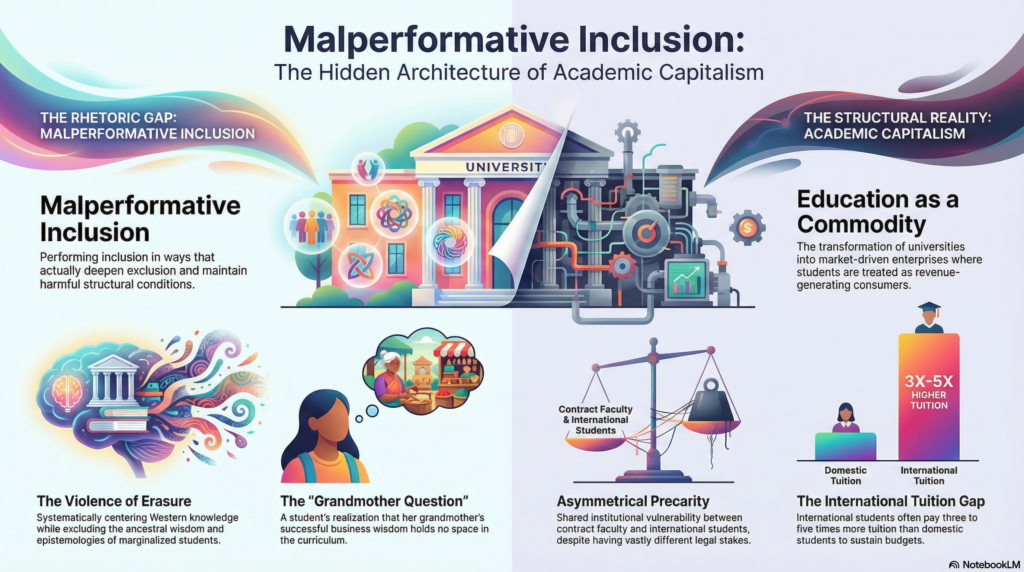

I think about the grandmother question. Six weeks ago, a student raised her hand in my organizational leadership class and asked, “Where do I put grandmother’s business wisdom?” We had just finished a module on Western leadership theories: transformational leadership (Burns, 1978), transactional leadership (Bass, 1985), and servant leadership (Greenleaf, 1970). She had completed all the readings. She understood the frameworks. But her grandmother, who had built and sustained a successful textile business in her home country for four decades, did not appear anywhere in our curriculum. The student wanted to know where that knowledge belonged.

I did not have a good answer. The truth is that the curriculum I was teaching, the curriculum I had been hired to deliver, held no space for her grandmother. Paulo Freire (2018), whose work on critical pedagogy I had studied but perhaps insufficiently lived, would recognize what was happening in that moment. He critiqued what he called the banking model of education, the educational approach where teachers deposit predetermined knowledge into passive student receptacles, treating learners as empty vessels to be filled rather than as knowers with their own expertise. The grandmother’s wisdom was not on file at this particular bank. It was denominated in a currency the institution refused to recognize.

That question catalyzed something in me that had been building for years. It made visible what I had been living but had not yet named: the violence of erasure that happens when institutions claim to value diversity while structurally excluding the knowledge systems that marginalized students bring with them.

I call this malperformative inclusion. The term extends Sara Ahmed’s (2012) work on non-performativity, her analysis of how institutional diversity statements often “do not do what they say” (p. 117). But malperformative inclusion goes further. It describes how institutions can actively demonstrate awareness of equity problems while simultaneously maintaining, and sometimes intensifying, the very structural conditions that produce harm. It is not that universities fail to achieve inclusion. It is that they perform inclusion in ways that actually deepen exclusion. They announce commitments to diversity in glossy brochures featuring international students’ smiling faces while charging those same students triple the tuition that domestic students pay. They celebrate multiculturalism in land acknowledgements while offering curricula that systematically centre Western epistemologies, the knowledge systems and ways of knowing that originate from European and North American intellectual traditions, as universal and neutral.

Conceptual Framework: Sources and Theoretical Lineage

| Concept or Theory | Associated Scholar(s) | Publication Year | Definition and Core Principles | Institutional Application or Critique | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretically grounded in Sara Ahmed, Judith Butler, and Henry Giroux | Theoretically grounded in Sara Ahmed, Judith Butler, Henry Giroux | 2024 | A condition in which institutions demonstrate awareness of equity and inclusion while sustaining or intensifying the structures that produce harm. Inclusion functions symbolically rather than materially, producing legitimacy without accountability. | Explains how universities celebrate diversity while relying on extractive tuition models, Western epistemologies, and disposable labour, particularly impacting international students and contract faculty. | Malperformative Inclusion and the Architecture of Academic Capitalism (Author manuscript); Ahmed (2012); Butler (1997); Giroux (2014) |

| Academic Capitalism | Sheila Slaughter & Gary Rhoades | 2004 | The transformation of universities into market-oriented enterprises where knowledge, students, and labour are commodified and aligned with revenue generation. | Frames international students as revenue streams and positions contingent faculty as flexible labour within neoliberal institutional logics. | Slaughter & Rhoades, Academic Capitalism and the New Economy |

| Asymmetrical Precarity (Author-developed concept) | Theoretically grounded in Judith Butler, Guy Standing | 2024 | A shared condition of insecurity across groups that carries unequal risks, consequences, and degrees of disposability. While precarity is relational, its impacts are unevenly distributed. | Differentiates the employment insecurity of contract faculty from the compounded risks faced by international students, including visa dependency, racialization, and deportability. | Malperformative Inclusion and the Architecture of Academic Capitalism (Author manuscript); Butler (2009); Standing (2011) |

| Precarity | Guy Standing; Judith Butler | 2011 | A state of chronic insecurity marked by unstable employment, income volatility, and institutional disposability, produced through neoliberal governance. | Describes long-term contract faculty labour conditions, including lack of benefits, uncertain renewal, and limited institutional voice. | Standing, The Precariat; Butler, Frames of War |

| Organizational Justice | Jerald Greenberg | 1987 | A framework emphasizing fairness through distributive, procedural, and interactional justice within organizations. | Serves as a normative benchmark against which the inequitable treatment of contract faculty and international students is assessed. | Greenberg (1987) |

| Non-performativity | Sara Ahmed | 2012 | The idea that institutional speech acts around diversity often fail to enact what they claim, functioning instead to block action. | The idea that institutional speech acts around diversity often fail to enact what they claim to do, functioning instead to block action. | Ahmed, On Being Included |

| Banking Model of Education | Paulo Freire | 1970 / 2018 | An educational model that treats learners as passive recipients of knowledge rather than active knowers. | Explains how institutions dismiss the prior learning, professional expertise, and non-Western knowledge of international students. | Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed |

| Care Ethics | Nel Noddings | 2013 | An ethical framework centred on relational responsibility, attentiveness, and responsiveness to others. | Exposes the contradiction between teaching care ethics and participating in systems that structurally refuse care. | Noddings, Caring |

| Transformational Leadership | James MacGregor Burns | 1978 | A leadership model focused on motivation, moral purpose, and leader–follower relationships. | Critiqued for privileging Western leadership ideals while marginalizing Indigenous, relational, and community-based knowledge systems. | Burns, Leadership |

Note. Malperformative inclusion and asymmetrical precarity are author-developed analytical concepts. They are theoretically grounded in scholarship on non-performativity (Ahmed, 2012), precarity (Butler, 2009; Standing, 2011), and academic capitalism (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004), and are advanced here to describe institutional conditions observed through Scholarly Personal Narrative and critical institutional analysis.

Thompson Rivers University, a small community university situated on unceded Secwépemc territory in British Columbia’s interior, operates within what Sheila Slaughter and Gary Rhoades (2004) theorize as academic capitalism. This concept describes the transformation of universities into market-driven enterprises where education becomes a commodity, students become consumers, and knowledge shifts from a public good to a private resource. As state funding for higher education has declined across Canada, institutions have adopted increasingly entrepreneurial behaviours to generate revenue. International students, who often pay three to five times as much as domestic students, have become essential to institutional survival.

But this “consumer” model applies unevenly. While domestic students receive substantial public subsidies, international students face the full volatility of the market. In January 2024, the federal government announced a study permit cap that reduced the number of international student permits by 35-45 percent. Universities that had built entire budget models on international student tuition suddenly faced a financial crisis. The cap created what I call an infrastructural visibility moment, a point in time when normally invisible structural dependencies become suddenly and undeniably visible. It revealed what had been naturalized: Canadian post-secondary institutions’ deep financial dependence on international students as sources of revenue rather than as learners with inherent worth.

I occupy a complicated position within this system. As contract faculty for nearly two decades, I have experienced precarity, the state of employment insecurity, income instability, and institutional disposability characteristic of contingent academic labour. I teach semester to semester, course by course, never certain whether my contracts will be renewed. I have limited access to professional development funds, research support, or decision-making authority within my department. Like my international student participants, I navigate structures that simultaneously need my labour and render me institutionally marginal.

But my precarity operates differently from theirs. I use the term asymmetrical precarity to name how we share structural vulnerabilities while experiencing vastly different stakes. My employment uncertainty does not threaten my legal right to remain in Canada. My institutional marginality does not compound with racialization, language barriers, visa dependency, or separation from family and community support systems. Our precarities resonate without being equivalent. This distinction matters. It keeps me accountable to the differences between our experiences, even as I recognize the structural parallels that connect us.

This research emerged from that Tuesday afternoon question about grandmothers and leadership. From sitting in this parking lot gathering the energy to walk into a building that extracts more than it returns. From seventeen years of watching international students navigate an institution that recruits them aggressively while structurally marginalizing their presence.

What follows in this dissertation is my attempt to document what I have witnessed. To position international students as the experts on their own experiences, as institutional ethnographers who can teach us what we have failed to see. To create methodological space where their photographs, their words, their theories about how the university operates become legitimate scholarly knowledge rather than complaints to be managed.

I put the coffee cup in the holder and turn the key in the ignition. The engine starts. I will walk into that classroom and teach organizational justice and care ethics. But I will do it differently now. I will teach the theories and the contradictions. I will name what the institution asks us not to see.

The work begins here.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed (50th anniversary ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. (Original work published 1970)

Greenberg, J. (1987). A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 9-22. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1987.4306437

Greenleaf, R. K. (1970). The servant as leader. Robert K. Greenleaf Center.

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A relational approach to ethics and moral education (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.